Studies |

"When you run into something interesting, drop everything else and study it."

– B. F. Skinner |

2D vs. 3D Stimuli |

INTRODUCTION

In this study, participants encountered a single scene (stimulus) that was presented in three distinctly different forms: reality, a photograph, and a line drawing. Each participant made three drawings, one from each stimulus, at seven-day intervals. The order in which the stimuli were presented was random.

In this study, participants encountered a single scene (stimulus) that was presented in three distinctly different forms: reality, a photograph, and a line drawing. Each participant made three drawings, one from each stimulus, at seven-day intervals. The order in which the stimuli were presented was random.

RATIONALE

DRAWING FROM REALITY, FROM A PHOTOGRAPH, AND FROM A DIAGRAM.

While a drawing process often involves the use of observed stimuli, implicit in the notion of drawing from observation is that the observed is real rather than a two-dimensional representation such as a photograph or a diagram.

Being able to read and interpret the real world onto a flat surface entails estimating things such as object(s) size and separation. Successful completion of this process requires organizational agreement in all three dimensions. In stimuli such as a photograph or a diagram, the problem of reading and interpreting depth has already been resolved in terms of the other two dimensions: nearer and further exist on the picture plane merely as up and down or left and right.

It is not uncommon to encounter students whose experience is restricted to drawing while ‘observing’ two-dimensional stimuli. Augmenting such experience with true observational drawing is a challenge for such students as working from reality can feel like a step backwards in terms of process control and achieving a satisfying spatial illusion. Nonetheless, those who teach observational drawing know that the edited and pre-determined view presented by a photograph, diagram or other two-dimensional stimulus is essentially restricting to both process and to outcomes.

Interested in testing student response when drawing from a common source presented as three distinctly different forms of stimulus, a study involving six participants was conducted in NSCAD Drawing Lab.

DRAWING FROM REALITY, FROM A PHOTOGRAPH, AND FROM A DIAGRAM.

While a drawing process often involves the use of observed stimuli, implicit in the notion of drawing from observation is that the observed is real rather than a two-dimensional representation such as a photograph or a diagram.

Being able to read and interpret the real world onto a flat surface entails estimating things such as object(s) size and separation. Successful completion of this process requires organizational agreement in all three dimensions. In stimuli such as a photograph or a diagram, the problem of reading and interpreting depth has already been resolved in terms of the other two dimensions: nearer and further exist on the picture plane merely as up and down or left and right.

It is not uncommon to encounter students whose experience is restricted to drawing while ‘observing’ two-dimensional stimuli. Augmenting such experience with true observational drawing is a challenge for such students as working from reality can feel like a step backwards in terms of process control and achieving a satisfying spatial illusion. Nonetheless, those who teach observational drawing know that the edited and pre-determined view presented by a photograph, diagram or other two-dimensional stimulus is essentially restricting to both process and to outcomes.

Interested in testing student response when drawing from a common source presented as three distinctly different forms of stimulus, a study involving six participants was conducted in NSCAD Drawing Lab.

METHODS

We did not attempt to measure attention and perception directly in our collaboration. We focused on action (i.e., eye movements and hand movements [drawing behavior]) as a window on the working of attention in the drawing-from-observation process and on how that process is influenced by training and practice.

Our study was undertaken to record, measure and analyze that part of the drawing process that is often the most difficult for the novice: Where and how does one begin a drawing? To answer these questions, the researchers undertook to record and compare where (a) expert artists and (b) novice artists look and draw during the first few minutes of the drawing process.

A task was designed in which participants were given three minutes to draw a three-dimensional scene of nine simple geometric objects. Eye and hand movements were captured with an eye tracker and video camera.

Our study was less “experimental” than it was “observational.” That is, we were not so much manipulating a variable (cause) to determine how it would affect behavior (effect), as we were simply setting up a controlled situation intended to elicit the natural processes of drawing from observation so that we could observe, record, classify, measure and analyze our participants’ eye movements and drawing behaviors.

Participants

All participants, four female and two male, were right handed. Three were between the ages of 17 – 24 and three between 25 – 29 years. One wore contact lenses while five required no form of corrective eyewear. Drawing experience ranged from two declaring more than 10 years of experience, one between 5 – 10 years experience, and three with less than 2 years experience.

When asked to rate the frequency of using observational drawing as part of their regular art practice where 1 represents never, 4 sometimes and 7 always, one participant checked 4, three 5 and two 6. None claimed drawing from observation as something that is always part of their practice. However, all had completed entry-level courses in observational drawing and could, therefore, be expected to be familiar with a variety of approaches to drawing as well as to the use of different drawing materials.

As an indicator of personal confidence, participants were asked to rate how often they are satisfied with the results of their observational drawing where 1 represents never satisfied, 4 sometimes satisfied and 7 always satisfied. None expressed total satisfaction, two reported 6, one 5, two 4 with one indicating a 3 which was below a level of being sometimes satisfied.

Apparatus

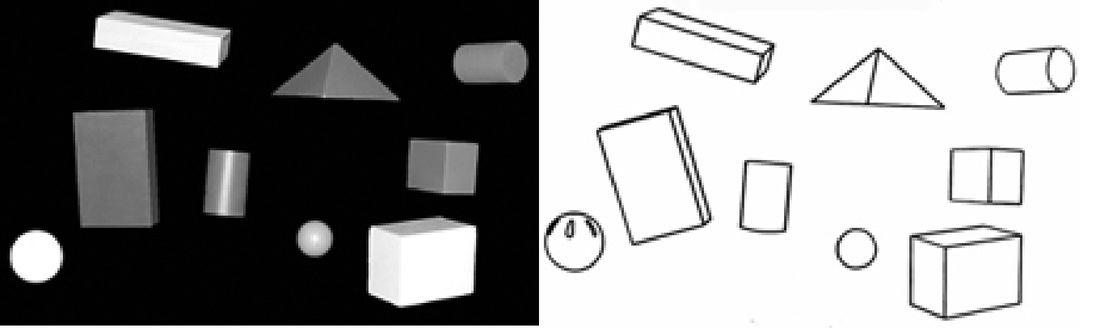

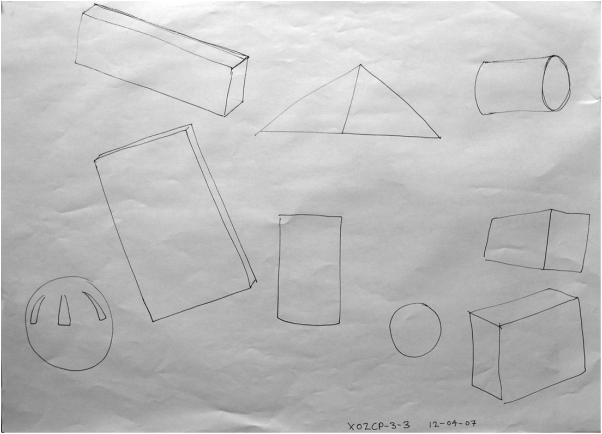

The stimulus – eight, geometric forms in various shades of grey – was presented as real objects viewed against a black background (A), as a life-size black and white, half-tone photograph (B), and as a life-size black on white diagrammatic line drawing (C).

We did not attempt to measure attention and perception directly in our collaboration. We focused on action (i.e., eye movements and hand movements [drawing behavior]) as a window on the working of attention in the drawing-from-observation process and on how that process is influenced by training and practice.

Our study was undertaken to record, measure and analyze that part of the drawing process that is often the most difficult for the novice: Where and how does one begin a drawing? To answer these questions, the researchers undertook to record and compare where (a) expert artists and (b) novice artists look and draw during the first few minutes of the drawing process.

A task was designed in which participants were given three minutes to draw a three-dimensional scene of nine simple geometric objects. Eye and hand movements were captured with an eye tracker and video camera.

Our study was less “experimental” than it was “observational.” That is, we were not so much manipulating a variable (cause) to determine how it would affect behavior (effect), as we were simply setting up a controlled situation intended to elicit the natural processes of drawing from observation so that we could observe, record, classify, measure and analyze our participants’ eye movements and drawing behaviors.

Participants

All participants, four female and two male, were right handed. Three were between the ages of 17 – 24 and three between 25 – 29 years. One wore contact lenses while five required no form of corrective eyewear. Drawing experience ranged from two declaring more than 10 years of experience, one between 5 – 10 years experience, and three with less than 2 years experience.

When asked to rate the frequency of using observational drawing as part of their regular art practice where 1 represents never, 4 sometimes and 7 always, one participant checked 4, three 5 and two 6. None claimed drawing from observation as something that is always part of their practice. However, all had completed entry-level courses in observational drawing and could, therefore, be expected to be familiar with a variety of approaches to drawing as well as to the use of different drawing materials.

As an indicator of personal confidence, participants were asked to rate how often they are satisfied with the results of their observational drawing where 1 represents never satisfied, 4 sometimes satisfied and 7 always satisfied. None expressed total satisfaction, two reported 6, one 5, two 4 with one indicating a 3 which was below a level of being sometimes satisfied.

Apparatus

The stimulus – eight, geometric forms in various shades of grey – was presented as real objects viewed against a black background (A), as a life-size black and white, half-tone photograph (B), and as a life-size black on white diagrammatic line drawing (C).

Procedure

Participants were instructed to draw using lines only. Each participant made three timed (10 minute) drawings, with a seven-day period between each drawing. The presentation order of the stimuli was unique to each participant thus: A,B,C; A,C,B; B,A,C; B,C,A; C,A,B; C,B,A.

A common paper size (46h cm x 56w cm) was affixed to a static easel and an eraser and selection of pencils (B, 2B, 4B & 6B) was provided.

After finishing the third drawing, each participant completed a questionnaire designed to draw out information that included personal attributes, drawing experience, etc.

RESULTS

Evaluation of the drawings was qualitative rather than quantitative and was carried out by the researcher and Mathew Reichertz who, although a current member of the research team, was not involved in the design and implementation of original tests. He was therefore, able to contribute an unbiased view of the final drawings.

Questions pertaining to the accuracy of each drawing were set aside because, while it was possible to control where each participant sat, individual eye levels varied according to personal height thereby causing the planes of the objects to present differently from one participant to another. Simply, there was no reliable way to reestablish each participant’s eye-level.

For purposes of evaluation, the drawings were placed side by side as sets of three made by each participant, and then as groups of six made from each of the three stimuli.

In each group of six drawings from a single stimulus, no similarities were clearly identified by the reviewers; although it was noted that stronger, perhaps more intuitive compositions were present in the set of drawing made from reality: full 3D.

While there were some differences within individual sets of three drawings, of the 18 drawings completed by the six participants, only one set of three suggested that the participant was responding differently to each stimulus: that is, the styles of marking making suggest differences that reflect qualities within the stimulus. This particular participant drew from the stimuli in the order – B, A, C (photograph, reality, diagram).

Drawings

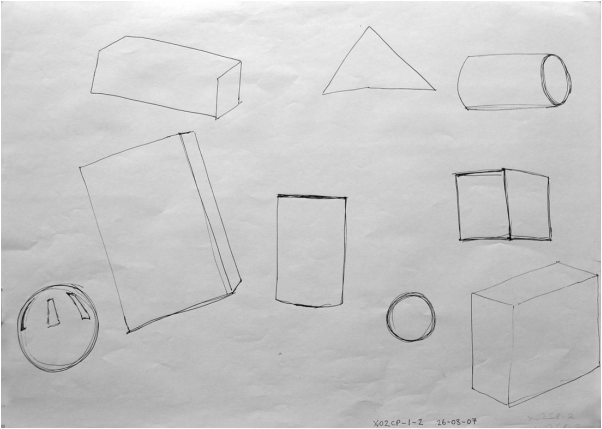

In this first drawing – made from the photograph – differences in contrast along the edges of the planes are illustrated by different densities of mark making. Of particular note are the missing marks: the absence of a line representing the division between two planes. For example, the top left rectangular form where almost no tonal difference is detectable between the front and top planes, the edge of the plane is implied only; likewise in the pyramid form. In the photograph, one has to look very closely to see any tonal difference. At the distance from which the photograph was viewed, no difference is discernible. This is equally true of other objects within the scene.

Evaluation of the drawings was qualitative rather than quantitative and was carried out by the researcher and Mathew Reichertz who, although a current member of the research team, was not involved in the design and implementation of original tests. He was therefore, able to contribute an unbiased view of the final drawings.

Questions pertaining to the accuracy of each drawing were set aside because, while it was possible to control where each participant sat, individual eye levels varied according to personal height thereby causing the planes of the objects to present differently from one participant to another. Simply, there was no reliable way to reestablish each participant’s eye-level.

For purposes of evaluation, the drawings were placed side by side as sets of three made by each participant, and then as groups of six made from each of the three stimuli.

In each group of six drawings from a single stimulus, no similarities were clearly identified by the reviewers; although it was noted that stronger, perhaps more intuitive compositions were present in the set of drawing made from reality: full 3D.

While there were some differences within individual sets of three drawings, of the 18 drawings completed by the six participants, only one set of three suggested that the participant was responding differently to each stimulus: that is, the styles of marking making suggest differences that reflect qualities within the stimulus. This particular participant drew from the stimuli in the order – B, A, C (photograph, reality, diagram).

Drawings

In this first drawing – made from the photograph – differences in contrast along the edges of the planes are illustrated by different densities of mark making. Of particular note are the missing marks: the absence of a line representing the division between two planes. For example, the top left rectangular form where almost no tonal difference is detectable between the front and top planes, the edge of the plane is implied only; likewise in the pyramid form. In the photograph, one has to look very closely to see any tonal difference. At the distance from which the photograph was viewed, no difference is discernible. This is equally true of other objects within the scene.

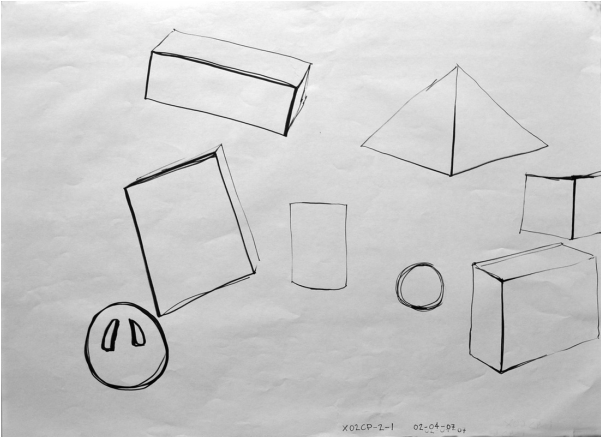

In the second drawing – made from life – the participant chose to employ stronger, darker lines within each object, as the means to suggest closer proximity to the picture plane. This is apart from existing tonal variations within the stimulus and is consistent in a way that suggests an attempt at a simplified and more stylistic interpretation of complexity: a familiar and often learned strategy for depicting spatial variations.

In the third and final drawing – made from the diagram – no variation in line quality exists. Indeed, like in the diagram itself, absolute consistency in the quality of the line is the dominant stylistic feature.

Compositionally – how the objects are placed within the page – the first and third drawings (from the photograph and from the diagram) are closest to the composition of the stimulus that was centered within the viewing plane with equal spacing around the edges. In the case of the second drawing, the composition has slid to the right but with the result that the sense of space, depth and, perhaps, interest is enhanced. At least, that was the opinion of the reviewers.

DISCUSSION

When drawing from a two-dimensional stimulus, compositional consistency between a drawing and the stimulus is stronger and likely attributable to the fact that placement on the page is not complicated by the challenge of estimating relationships of depth and distance between objects and from the picture plane. The space around the group of objects is relatively consistent as it can be read in terms of width and height only, and the objects themselves may be read and represented as simple contiguous shapes rather than as complex forms with planes that vary by tone as well as shape.

Given that all participants have experience drawing from observation that will have included consideration of line as a means to carry meaning beyond that of mere shape, it is, perhaps, surprising that more was not made of line variation as a means of achieving spatial illusion and visual interest.

Postscript

As with other studies in the Drawing Laboratory, variation in participant drawing-style, drawing experience and subject interest appears to militate against shared and consistent approaches to means and to ends.

For the drawing researcher hoping to identify significant patterns or trends in process and product, the individuality of the emerging artist may serve only to frustrate. However, the opportunity to witness, slow down (as a video record), and review individual drawing behaviors continues to pique the interest of the researchers and we would welcome ideas for further investigation.

N.B. A graduate student in architecture at a sister institution was one of the six participants and kept a journal about her drawing experience that included reference to her participation in the study. A link to the journal can be found here.

When drawing from a two-dimensional stimulus, compositional consistency between a drawing and the stimulus is stronger and likely attributable to the fact that placement on the page is not complicated by the challenge of estimating relationships of depth and distance between objects and from the picture plane. The space around the group of objects is relatively consistent as it can be read in terms of width and height only, and the objects themselves may be read and represented as simple contiguous shapes rather than as complex forms with planes that vary by tone as well as shape.

Given that all participants have experience drawing from observation that will have included consideration of line as a means to carry meaning beyond that of mere shape, it is, perhaps, surprising that more was not made of line variation as a means of achieving spatial illusion and visual interest.

Postscript

As with other studies in the Drawing Laboratory, variation in participant drawing-style, drawing experience and subject interest appears to militate against shared and consistent approaches to means and to ends.

For the drawing researcher hoping to identify significant patterns or trends in process and product, the individuality of the emerging artist may serve only to frustrate. However, the opportunity to witness, slow down (as a video record), and review individual drawing behaviors continues to pique the interest of the researchers and we would welcome ideas for further investigation.

N.B. A graduate student in architecture at a sister institution was one of the six participants and kept a journal about her drawing experience that included reference to her participation in the study. A link to the journal can be found here.