Studies |

"When you run into something interesting, drop everything else and study it."

– B. F. Skinner |

Lighting (Pilot Study) |

INTRODUCTION

How a form is illuminated makes a difference to how it is perceived for purposes of drawing. This assumption, shared by the researchers, both of whom are experienced artists and teachers, underpins the nature of drawing tasks completed by two advanced level, post-secondary art students. Working from a common stimulus that was lit in two distinctly different ways, the participants drew for a predetermined period of time while being observed first-hand and digitally recorded. On completion of drawings carried out seven days apart, the digital recordings and the drawings themselves were compared. Detailed analysis, in particular of the recordings, generated the most informative data, which suggests that, when teaching about the perception and depiction of form, assumptions regarding light’s influence on the drawing process may be less significant than expected.

How a form is illuminated makes a difference to how it is perceived for purposes of drawing. This assumption, shared by the researchers, both of whom are experienced artists and teachers, underpins the nature of drawing tasks completed by two advanced level, post-secondary art students. Working from a common stimulus that was lit in two distinctly different ways, the participants drew for a predetermined period of time while being observed first-hand and digitally recorded. On completion of drawings carried out seven days apart, the digital recordings and the drawings themselves were compared. Detailed analysis, in particular of the recordings, generated the most informative data, which suggests that, when teaching about the perception and depiction of form, assumptions regarding light’s influence on the drawing process may be less significant than expected.

RATIONALE

Context

Since the 15th century, those who draw and paint from life have known that presenting the effects of light in a manner that is constant is a key to creating coherent and credible representations of space and form. Even today, drawing instruction, whether from books or in a studio setting, usually includes exercises that underscore the significance of understanding and applying the effects of light.

Question

For purposes of this study, the researchers were concerned with the observation and analysis of how and when information about light enters the drawing process? Of particular interest is whether significant differences in how a stimulus is lit affect strategies and behaviours related to drawing. The hypothesis was that relative to a diffusely lit object, a directly lit object that presents areas of strong contrast would result in a drawing process that focuses attention on light and shadow. What the researchers were looking for was a difference in how drawings were started and how they progressed based on differences in lighting.

Context

Since the 15th century, those who draw and paint from life have known that presenting the effects of light in a manner that is constant is a key to creating coherent and credible representations of space and form. Even today, drawing instruction, whether from books or in a studio setting, usually includes exercises that underscore the significance of understanding and applying the effects of light.

Question

For purposes of this study, the researchers were concerned with the observation and analysis of how and when information about light enters the drawing process? Of particular interest is whether significant differences in how a stimulus is lit affect strategies and behaviours related to drawing. The hypothesis was that relative to a diffusely lit object, a directly lit object that presents areas of strong contrast would result in a drawing process that focuses attention on light and shadow. What the researchers were looking for was a difference in how drawings were started and how they progressed based on differences in lighting.

METHODS

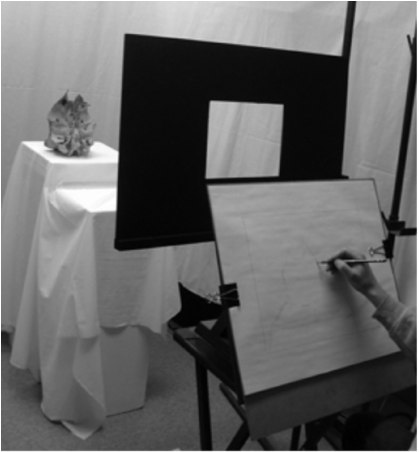

The design of the task sought to reveal some of the choices that the participants made when confronted by the problem of drawing a single, complex form (the stimulus) viewed under distinctly different lighting conditions. The stimulus, a lower jawbone of a large, unidentified mammal was oriented vertically on a white, horizontal surface and seen against a white background as shown in Figure A where the stimulus is lit neutrally. By orienting the stimulus in this way, the researchers intended to present it as a novel rather than as a familiar object.

Participants

The participants were two university level, advanced drawing and painting students.

Design

Two participants were asked to draw the figure in both diffusely lit and directly lit lighting, in separate drawing sessions, spaced a week apart. The participants were unaware that they would be drawing the same figure in different lighting conditions only that they would be coming back for a second drawing session.

The first participant saw the figure first in incandescent light (directly lit from the side) then in the second session in fluorescent light (diffusely lit). The second participant saw the figure in reverse order.

The design of the task sought to reveal some of the choices that the participants made when confronted by the problem of drawing a single, complex form (the stimulus) viewed under distinctly different lighting conditions. The stimulus, a lower jawbone of a large, unidentified mammal was oriented vertically on a white, horizontal surface and seen against a white background as shown in Figure A where the stimulus is lit neutrally. By orienting the stimulus in this way, the researchers intended to present it as a novel rather than as a familiar object.

Participants

The participants were two university level, advanced drawing and painting students.

Design

Two participants were asked to draw the figure in both diffusely lit and directly lit lighting, in separate drawing sessions, spaced a week apart. The participants were unaware that they would be drawing the same figure in different lighting conditions only that they would be coming back for a second drawing session.

The first participant saw the figure first in incandescent light (directly lit from the side) then in the second session in fluorescent light (diffusely lit). The second participant saw the figure in reverse order.

Apparatus

The participants were seated at an easel, 120cm from the stimulus, which was viewed through a black ‘window’ frame with an opening size of 25cm wide x 20cm high. The frame was vertically mounted close to midway between the participant and the stimulus: 50 cm from the participant and 70 cm from the stimulus. Use of a window frame was intended primarily to stabilize the participants’ viewing position. For the drawings where incandescent sidelight was used, the window frame also served to hide the light source. A rectangle, proportional to the window through which the participants viewed the stimulus was pre-drawn on each sheet of drawing paper, provided a common drawing area. An eraser and several 6B (very soft) pencils were provided as drawing tools.

The participants were seated at an easel, 120cm from the stimulus, which was viewed through a black ‘window’ frame with an opening size of 25cm wide x 20cm high. The frame was vertically mounted close to midway between the participant and the stimulus: 50 cm from the participant and 70 cm from the stimulus. Use of a window frame was intended primarily to stabilize the participants’ viewing position. For the drawings where incandescent sidelight was used, the window frame also served to hide the light source. A rectangle, proportional to the window through which the participants viewed the stimulus was pre-drawn on each sheet of drawing paper, provided a common drawing area. An eraser and several 6B (very soft) pencils were provided as drawing tools.

Procedure

Prior to commencement of drawing, the stimulus was hidden from view by a white board placed between the black frame and the stimulus. At the centre of the white board was a target-area that coincided with the placement of the hidden stimulus. This provided a focal point by which the participants could align themselves in anticipation of beginning the drawing task.Written instructions were provided to the participants:

PRIOR TO STARTING THE DRAWING PLEASE ENSURE THAT:

The target is centred in the black frame; and

You are at a comfortable distance from the drawing surface.

YOU SHOULD ALSO KNOW THAT:

You will be making a 10-minute drawing; and that

You will be using a 6B pencil and kneadable eraser.

FYI

The pre-drawn frame on the paper is in proportion to the black window frame.

You will be notified at the 5 and 8 minute marks as well as at 10 minutes; and

Your drawing will be retained for research purposes.

When a participant indicated readiness to begin the task, the white board was removed, video documentation was initiated and a stopwatch started to time a ten-minute drawing session.

At the first session, Participant 1 drew from the stimulus lit with ‘general’ fluorescent lighting, while Participant 2 drew from the stimulus lit by a single incandescent light source set up high and to the left of the stimulus.

As previously advised, participants were notified at three time markers. This strategy was intended to minimize anxiety that may have resulted from feeling ‘rushed’ to complete a drawing within a relatively short timeframe. It is worth noting that at the 10-minute mark each participant was invited to continue working if they felt the drawing was incomplete. In all four drawing sessions, the offer to continue beyond the allotted time was declined.

Upon completion of a drawing, each participant was invited to return to the laboratory seven days later for the purpose of making a second drawing. They were not told anything about the new task and were asked not to discuss the previous task. When the participants returned to the laboratory, the process was repeated, the only difference being that the lighting was changed: the participant who drew the stimulus lit by fluorescent light next encountered the stimulus lit by direct incandescent light and the participant who drew under direct incandescent light was confronted by the more general fluorescent lighting.

Upon completion of the second drawing, each participant was asked to fill out a short questionnaire the answers to which were intended to supplement the evidence provided by the digital record and by the finished drawings. The participants were asked:

- Can you describe the difference between the experiences of making each drawing?

- Did you approach the drawing differently because of the difference in lighting?

- Can you comment on the subject matter as it may have influenced how you worked?

- To what extend do you think that the drawing tool influenced process?

- As much as we hoped that the set-up presented to you would have felt like a familiar and comfortable drawing situation, was there anything about the set-up that changed how you would typically draw from observation?

- Do you think that the difference in lighting changed the way you approached the task?

- Did memory affect how you approached the second drawing?

- As you know this to be is a pilot study, do you have any advice regarding how to make the experience better, clearer, etc?

RESULTS

The Drawings

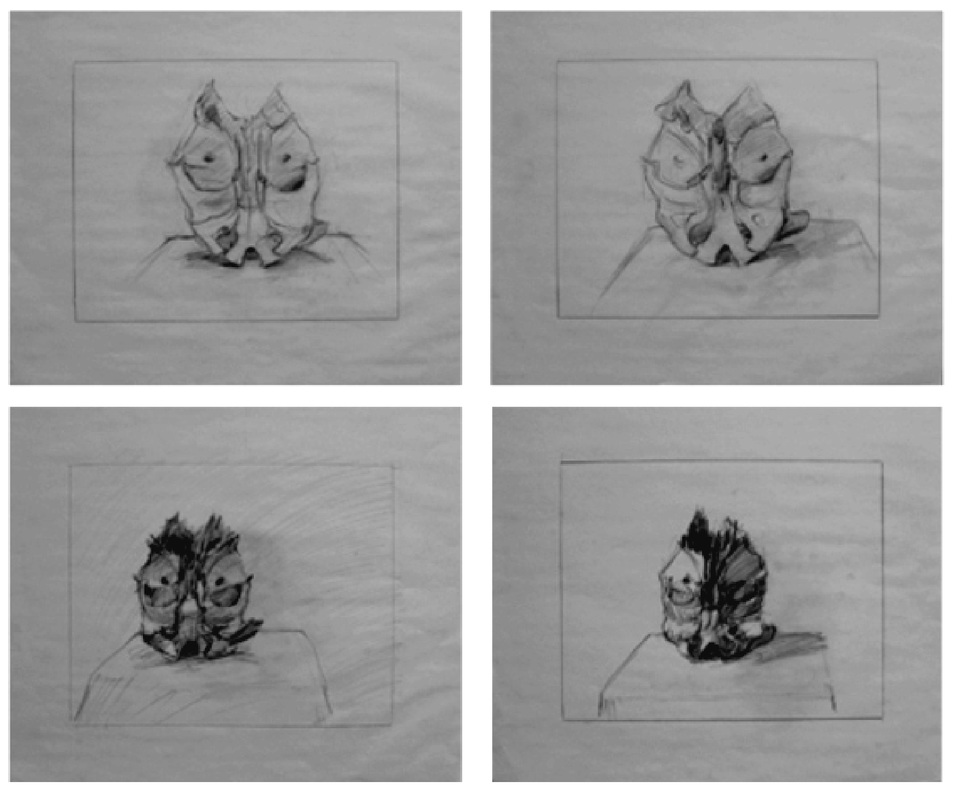

The top row shows the two drawings by Participant 1; the bottom row shows the two drawings by Participant 2. Drawings of the object when diffusely lit are shown on the left; when directly lit are shown on the right. The upper left and lower right drawing were drawn first

For purposes of analysis, the drawings were paired and reviewed side-by-side. This was done first by participant and then by lighting. The reader can view the 4 drawings with these comparisons in mind in Figure E. Comparison between participants (rows in Figure E) demonstrates differences of image size and mark making: Participant 1 portrayed the stimulus larger and rendered it with smaller, less defined marks than did participant 2 who portrayed the stimulus smaller and made marks that were more energetic. It is apparent from the finished drawings that each participant is making choices about composition and style that result in a similar product. This similarity demonstrates that the hypothesis – significant differences in stimulus-lighting would result in different approaches to the drawing process – may be invalid. It was the digital records of the drawing processes that provided an opportunity to closely review how each drawing evolved and whether attention to the effect of light was a more significant influence than was suggested by the outcome alone.

The Drawings

The top row shows the two drawings by Participant 1; the bottom row shows the two drawings by Participant 2. Drawings of the object when diffusely lit are shown on the left; when directly lit are shown on the right. The upper left and lower right drawing were drawn first

For purposes of analysis, the drawings were paired and reviewed side-by-side. This was done first by participant and then by lighting. The reader can view the 4 drawings with these comparisons in mind in Figure E. Comparison between participants (rows in Figure E) demonstrates differences of image size and mark making: Participant 1 portrayed the stimulus larger and rendered it with smaller, less defined marks than did participant 2 who portrayed the stimulus smaller and made marks that were more energetic. It is apparent from the finished drawings that each participant is making choices about composition and style that result in a similar product. This similarity demonstrates that the hypothesis – significant differences in stimulus-lighting would result in different approaches to the drawing process – may be invalid. It was the digital records of the drawing processes that provided an opportunity to closely review how each drawing evolved and whether attention to the effect of light was a more significant influence than was suggested by the outcome alone.

Digital Record

Analysis of the digital record was organized in the same way as that of the finished drawings. They were paired and analyzed side-by-side and, in each case, every care was taken to ensure that time markers were kept as consistent as possible. Knowing how each drawing had progressed in time is important. Only when, at a time marker, a participant’s hand obscured the image was the marker moved forward or back to reveal the drawing surface. In this way, synchronization at each marker was achieved to within one or two seconds. For purposes of comparison and narrative continuity, it was deemed helpful to mark significant events such as completion of outline, inclusion of background and the establishment of drawing style. However, researchers’ observations at the markers are designed to privilege events pertaining to the portrayal of light.

As with the comparison between the finished drawings, review of the digital records points to relative consistency in the processes used by each participant. Even though the drawings were made seven days apart and the lighting was changed substantially, in terms of process, the participants undertook similar drawing tasks at similar stages. For example, participant 2 began to address light both generally and specifically at 2.5 min in both drawings. Likewise, participant 1 introduced cast shadow in both drawings between 4 and 4.5 min. It appears that, particularly at early stages of the drawings and regardless of how the stimulus was illuminated, each participant employed a common strategy for reading and recording the stimulus.

Most significantly, at the 1.5 min in all four drawings, the outline of the form had been established. It is only when mark making changed from line to shading that information about light clearly entered the drawing process. In all four drawings, the shadow at the lower part of the stimulus was included by 2 min. But, as the primary focus of all four drawings up to this time was to define the stimulus using line, the choice of this particular shading event may have more to do with grounding the composition than with making distinctions between the varying effects of light. It is not until 2.5 min, after the overall shape had been established, that Participant 2’s behavior primarily involved shading. By 4 mins and in all four drawings, the style of the finished drawing had been established.

These patterns suggest that our participants developed a structural understanding of the stimulus prior to attending to its lighting conditions. It was as if, before they began to apply the effects of light, they sought a mental image of the object abstracted from the lighting conditions.

Questionnaire

The purpose of the questionnaire was threefold: first to ask participants to reflect upon changes in lighting; second to ask about the design of the task; and finally to seek advice as to how the task could be better organized. In terms of the response to light, the primary focus of the study, Participant 1 ‘did not notice’ a change in lighting and Participant 2 noticed ‘but not a whole lot’. Although participant 2 went on to say that under incandescent light it was ‘easier to recognize differences’. Interestingly, Participant 1 who claimed not to notice variations in light also commented that, when making the second drawing, I ‘remembered variations in shadow’

DISCUSSION

It seems clear that, for these two participants, completing the task did not, as our working hypothesis predicted, involve privileging portrayal of form through particular attention to light and shadow. Indeed, if the participants’ written report of their memories of the process are accurate, variation in lighting made no difference in how they approached each task and the

analysis of the digital documentation would appear to support this conclusion. Regardless of the lighting conditions, the participants began their drawings in much the same way and at much the same rate.

The researchers had expected to see a difference in how the participants started their drawings. The thought was that areas of greatest contrast would be the first things that drew the participants’ attention. For example, in Fig. D (direct incandescent light), the shadow on the stimulus is adjacent to the cast shadow in a way that may, if one squints at the image, cause the shadows to blend together, becoming one dark shape. Our expectation was that visual phenomena like this, which could be used to define the stimulus’s relationship to its surroundings, would be one of the first to be committed to paper. What actually happened with both participants was that this combined shape was not attended to until the outline(s) of the stimulus was confidently understood separate from its surroundings. Given that form and spatial information are generally apprehended, through value change, such an approach would appear counterintuitive. Seeing the shadow on the stimulus connected to its cast shadow would have made a convincing representation of form easier to accomplish. However, ease of artistic representation may be coming into conflict with the kind of cognitive strategies meant for survival. Allowing for a productive confusion about where a form begins and where it ends would not be a good survival strategy when being stalked by a predator.

Implications for Further Study

Acknowledgement that there are substantial differences between basic perceptual survival strategies and the most efficacious way to approach illusionistic representation may have important pedagogical implications. There is often a turning point for a novice drawer akin to finding one’s balance on a bicycle: the new understanding comes suddenly and is difficult to describe verbally. It could be that this understanding has to do with relinquishing perceptual survival strategies in exchange for strategies that are helpful for making convincing representations. Understanding where and how these two cognitive modes come into conflict may help develop a more efficacious curriculum. But, having designed the study as a pilot with only two participants, the researches anticipated that further testing would be required to confirm or deny the study’s findings.

A variety of possible changes come to mind. The stimulus could be a simpler form. Both participants commented that it was complex and, therefore, difficult to draw in the allotted time. Presenting a more manageable drawing task might result in different decisions at the beginning stages of the drawing. A different drawing tool(s) could be used. One participant commented that the ‘pencil doesn’t achieve lighting quickly’ and the other observed that while a ‘universal tool’, a pencil ‘caters to contour drawing’. It could be that using a pencil to describe form encourages a process akin to that used in computer animation where forms are generated from points that become lines, that become wire-frames and, in turn, are finally texture and light-wrapped. Using drawing materials such as charcoal or brush and ink could have a significant impact on how the drawing task unfolds. More dramatic differences in lighting could be applied. While, as we designed the study, we felt that the change in lighting was significant, the participants claimed not to have noticed, or to have barely noticed, any difference. Finally, novice drawers might be tested. Perhaps, because of their experience, our participants were able to represent the “true” object independently of how it was lit. Less experienced drawers, might be more or less influenced by the lighting differences.

In some ways, it may appear that experienced instructors completely missed the mark by basing a hypothesis upon their own experience of drawing. After all it is clear to most, if not all, practitioners that the act of drawing is both complex and varied. However for teaching purposes, understanding how we know and do may only be accomplished by breaking apart such complexity. Focusing a question on the affects of lighting is but one strategy.

Regardless of what changes might be implemented in future studies, this pilot study has given us the incentive to test a larger group of participants. Only with a larger group will it be possible to make inferences with confidence; inferences that might be useful in drawing instruction. Without further study and based upon this small sample, it could appear that an instructor who takes care to light a scene in order to create additional interest or to emphasize form, may be wasting both time and energy.

It seems clear that, for these two participants, completing the task did not, as our working hypothesis predicted, involve privileging portrayal of form through particular attention to light and shadow. Indeed, if the participants’ written report of their memories of the process are accurate, variation in lighting made no difference in how they approached each task and the

analysis of the digital documentation would appear to support this conclusion. Regardless of the lighting conditions, the participants began their drawings in much the same way and at much the same rate.

The researchers had expected to see a difference in how the participants started their drawings. The thought was that areas of greatest contrast would be the first things that drew the participants’ attention. For example, in Fig. D (direct incandescent light), the shadow on the stimulus is adjacent to the cast shadow in a way that may, if one squints at the image, cause the shadows to blend together, becoming one dark shape. Our expectation was that visual phenomena like this, which could be used to define the stimulus’s relationship to its surroundings, would be one of the first to be committed to paper. What actually happened with both participants was that this combined shape was not attended to until the outline(s) of the stimulus was confidently understood separate from its surroundings. Given that form and spatial information are generally apprehended, through value change, such an approach would appear counterintuitive. Seeing the shadow on the stimulus connected to its cast shadow would have made a convincing representation of form easier to accomplish. However, ease of artistic representation may be coming into conflict with the kind of cognitive strategies meant for survival. Allowing for a productive confusion about where a form begins and where it ends would not be a good survival strategy when being stalked by a predator.

Implications for Further Study

Acknowledgement that there are substantial differences between basic perceptual survival strategies and the most efficacious way to approach illusionistic representation may have important pedagogical implications. There is often a turning point for a novice drawer akin to finding one’s balance on a bicycle: the new understanding comes suddenly and is difficult to describe verbally. It could be that this understanding has to do with relinquishing perceptual survival strategies in exchange for strategies that are helpful for making convincing representations. Understanding where and how these two cognitive modes come into conflict may help develop a more efficacious curriculum. But, having designed the study as a pilot with only two participants, the researches anticipated that further testing would be required to confirm or deny the study’s findings.

A variety of possible changes come to mind. The stimulus could be a simpler form. Both participants commented that it was complex and, therefore, difficult to draw in the allotted time. Presenting a more manageable drawing task might result in different decisions at the beginning stages of the drawing. A different drawing tool(s) could be used. One participant commented that the ‘pencil doesn’t achieve lighting quickly’ and the other observed that while a ‘universal tool’, a pencil ‘caters to contour drawing’. It could be that using a pencil to describe form encourages a process akin to that used in computer animation where forms are generated from points that become lines, that become wire-frames and, in turn, are finally texture and light-wrapped. Using drawing materials such as charcoal or brush and ink could have a significant impact on how the drawing task unfolds. More dramatic differences in lighting could be applied. While, as we designed the study, we felt that the change in lighting was significant, the participants claimed not to have noticed, or to have barely noticed, any difference. Finally, novice drawers might be tested. Perhaps, because of their experience, our participants were able to represent the “true” object independently of how it was lit. Less experienced drawers, might be more or less influenced by the lighting differences.

In some ways, it may appear that experienced instructors completely missed the mark by basing a hypothesis upon their own experience of drawing. After all it is clear to most, if not all, practitioners that the act of drawing is both complex and varied. However for teaching purposes, understanding how we know and do may only be accomplished by breaking apart such complexity. Focusing a question on the affects of lighting is but one strategy.

Regardless of what changes might be implemented in future studies, this pilot study has given us the incentive to test a larger group of participants. Only with a larger group will it be possible to make inferences with confidence; inferences that might be useful in drawing instruction. Without further study and based upon this small sample, it could appear that an instructor who takes care to light a scene in order to create additional interest or to emphasize form, may be wasting both time and energy.