Studies |

"When you run into something interesting, drop everything else and study it."

– B. F. Skinner |

Drawing Stimuli Preferences Report

|

BACKGROUND

In my experience it is the practice of most, if not all, studio instructors to organize course introductions to include an exchange of information intended to familiarize everybody present with the nature of the student group. For the past few years, I have also included a more formal collection of information.

Knowing the experience and interests of each student enrolled is helpful when developing specific course content. To that end, when we first meet, I ask that each student fill out a short survey. This is done prior to reading the course outline; prior to expanding discussion of course content, and prior to students being afforded the opportunity to ask questions regarding my particular approach to teaching. By this means, I hope to gain the clearest, most reliable information about each student independent of how s/he may be influenced by course and instructor expectations.

Apart from having value as descriptions of individuals, student responses to the surveys also represents opportunities to gain an overall sense of a particular group as well as being able to compare them with other groups and across semesters.

The information collected represents the experience and opinions of 46 (3 groups) Foundation Drawing 1, and 76 (5 groups) Drawing 2 students. For the purpose of this report, only information related to student drawing experience, drawing genre and stimulus preference are discussed. No individual or group is identified beyond the level of study.

This is a report only, not advocacy. That said, I would welcome questions and/or comment. My hope is simply that others teaching first year drawing courses will find the following to be a useful context within which to reflect upon course content and teaching strategies.

SURVEY

Foundation Drawing – level one: 46 responses

Of the 46 students surveyed, 29 (63%) were taking post-secondary courses for the first time while 17 (37%) had completed some post-secondary study. In common, they shared the Admissions Committee’s evaluation that rated their drawing experience as appropriate to enrollment at the entry level. In terms of specific drawing experience, 16 (35%) students had attended some form of non-credit/continuing education drawing course prior to registering in Drawing 1. Many of these 16 students would have been identified through the admissions process as being in need of additional observational drawing experience and, as such, were instructed by the Admissions Committee to complete a Portfolio Preparation course as a condition of entry to the Foundation Program. 44 (96%) students indicated that, apart from assigned work, they draw for pleasure while 2 (4%) were candid enough to indicate no such practice.

Foundation Drawing – level two: 76 responses

The requirement for enrollment in Foundation Drawing 2 is the successful completion of Foundation Drawing 1 or evaluation, by the Admissions Committee and/or the Foundation Chair, that the application includes sufficient evidence of observational drawing skill for the applicant to be waived through level 1. In response to questions about when Drawing 1 was completed and also whether a waiver had been granted, the response totals may require further explanation. In particular, a student being waived through Drawing 1 may also have completed an equivalent course at another institution and, as such, was both recently completing Drawing 1 and having the requirement waived. Just 10 of 76 students reported that they had been waived through Drawing 1.

Of the students surveyed, 72 (95%) reported having completed Drawing 1 in the ‘last’ semester. This information is significant because long periods of drawing inactivity can negatively affect performance, particularly in the first few classes. Indeed, it is the experience of this drawing instructor that there can even be a marked difference between the initial performance of Drawing 2 students enrolled in Fall (September) courses and those enrolled in the Winter (January): in the latter, the interruption is less than 3 weeks while, in the former, the interruption is approximately 16 weeks. Completion of a first level course in the last semester may be considered relative when anticipating individual student drawing comfort and confidence.

On the question of whether they draw for pleasure and apart from assigned work, 16 of the 76 (21%) acknowledged that such was not their practice.

Preferences

Drawing takes many forms and people draw for a variety of reasons. At its root, it is a familiar and somewhat natural practice: mark making that normally involving pencil on paper. In this way, everybody draws. However, along the way, drawers often develop a preference for a particular starting point or stimulus. Having a sense of such preferences can be helpful when offering guidance. In the survey, students were asked to quantify their interest in the four most common stimuli.

In my experience it is the practice of most, if not all, studio instructors to organize course introductions to include an exchange of information intended to familiarize everybody present with the nature of the student group. For the past few years, I have also included a more formal collection of information.

Knowing the experience and interests of each student enrolled is helpful when developing specific course content. To that end, when we first meet, I ask that each student fill out a short survey. This is done prior to reading the course outline; prior to expanding discussion of course content, and prior to students being afforded the opportunity to ask questions regarding my particular approach to teaching. By this means, I hope to gain the clearest, most reliable information about each student independent of how s/he may be influenced by course and instructor expectations.

Apart from having value as descriptions of individuals, student responses to the surveys also represents opportunities to gain an overall sense of a particular group as well as being able to compare them with other groups and across semesters.

The information collected represents the experience and opinions of 46 (3 groups) Foundation Drawing 1, and 76 (5 groups) Drawing 2 students. For the purpose of this report, only information related to student drawing experience, drawing genre and stimulus preference are discussed. No individual or group is identified beyond the level of study.

This is a report only, not advocacy. That said, I would welcome questions and/or comment. My hope is simply that others teaching first year drawing courses will find the following to be a useful context within which to reflect upon course content and teaching strategies.

SURVEY

Foundation Drawing – level one: 46 responses

Of the 46 students surveyed, 29 (63%) were taking post-secondary courses for the first time while 17 (37%) had completed some post-secondary study. In common, they shared the Admissions Committee’s evaluation that rated their drawing experience as appropriate to enrollment at the entry level. In terms of specific drawing experience, 16 (35%) students had attended some form of non-credit/continuing education drawing course prior to registering in Drawing 1. Many of these 16 students would have been identified through the admissions process as being in need of additional observational drawing experience and, as such, were instructed by the Admissions Committee to complete a Portfolio Preparation course as a condition of entry to the Foundation Program. 44 (96%) students indicated that, apart from assigned work, they draw for pleasure while 2 (4%) were candid enough to indicate no such practice.

Foundation Drawing – level two: 76 responses

The requirement for enrollment in Foundation Drawing 2 is the successful completion of Foundation Drawing 1 or evaluation, by the Admissions Committee and/or the Foundation Chair, that the application includes sufficient evidence of observational drawing skill for the applicant to be waived through level 1. In response to questions about when Drawing 1 was completed and also whether a waiver had been granted, the response totals may require further explanation. In particular, a student being waived through Drawing 1 may also have completed an equivalent course at another institution and, as such, was both recently completing Drawing 1 and having the requirement waived. Just 10 of 76 students reported that they had been waived through Drawing 1.

Of the students surveyed, 72 (95%) reported having completed Drawing 1 in the ‘last’ semester. This information is significant because long periods of drawing inactivity can negatively affect performance, particularly in the first few classes. Indeed, it is the experience of this drawing instructor that there can even be a marked difference between the initial performance of Drawing 2 students enrolled in Fall (September) courses and those enrolled in the Winter (January): in the latter, the interruption is less than 3 weeks while, in the former, the interruption is approximately 16 weeks. Completion of a first level course in the last semester may be considered relative when anticipating individual student drawing comfort and confidence.

On the question of whether they draw for pleasure and apart from assigned work, 16 of the 76 (21%) acknowledged that such was not their practice.

Preferences

Drawing takes many forms and people draw for a variety of reasons. At its root, it is a familiar and somewhat natural practice: mark making that normally involving pencil on paper. In this way, everybody draws. However, along the way, drawers often develop a preference for a particular starting point or stimulus. Having a sense of such preferences can be helpful when offering guidance. In the survey, students were asked to quantify their interest in the four most common stimuli.

|

|

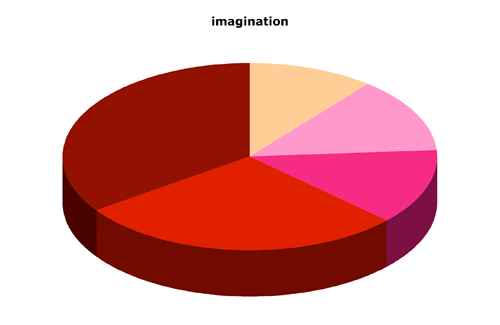

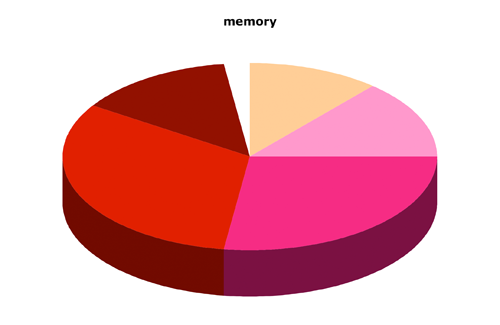

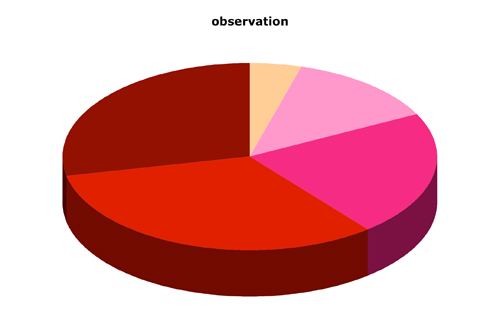

Question 7:

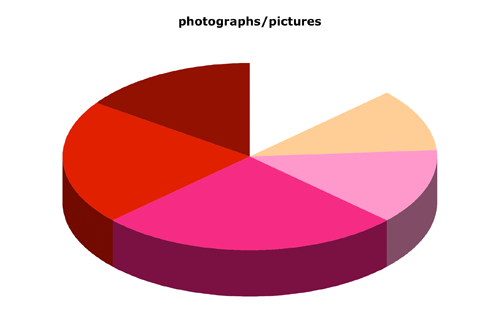

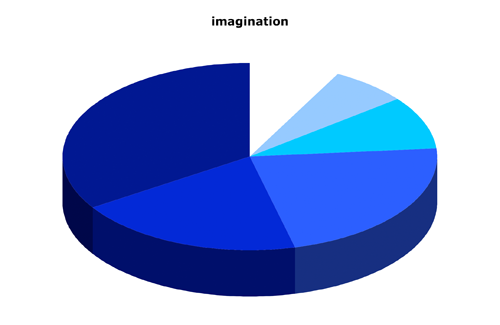

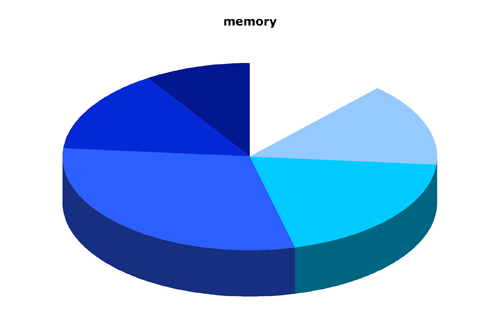

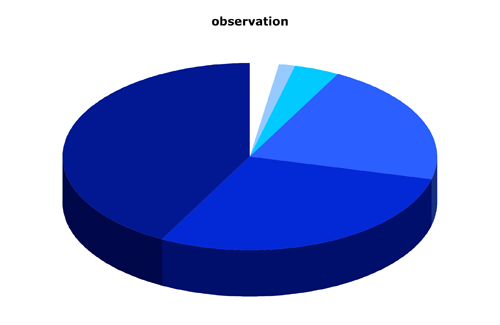

RATE THE FOLLOWING USING 0 FOR NOT AT ALL & 5 FOR VERY MUCH: I LIKE TO DRAW FROM: IMAGINATION MEMORY OBSERVATION 2D SOURCES (PHOTOS/PICTURES) |

Drawing 1

White = Not at all interested.

Darkest red = Very much interested.

White = Not at all interested.

Darkest red = Very much interested.

|

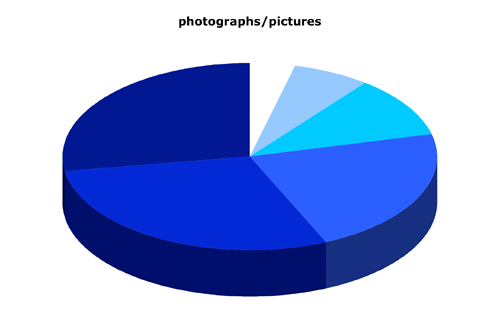

This is, perhaps, the most surprising set of responses as using photographs and pictures as source material is something that most students encounter as part of a pre-university art experience. Indeed, there was a time when many High School art departments seemed to focus significant portions of their programs on working from photographs. Students arrived in Foundation Drawing with sophisticated copying skills but relatively unsophisticated observation skills. Perhaps the relatively equal ratings in this set of responses is indicative of changing patterns in instruction and, therefore changing student experience and expectations. |

Drawing 2

White = Not at all interested.

Darkest blue = Very much interested.

Comparisons between Drawing 1 & 2 responses

Part of my interest in comparing responses from Drawing 1 and 2 is to understand the degree to which preferences change with experience. Throughout Drawing 1, students will have been immersed in drawing from observation with relatively little attention being afforded to other starting points. Subject matter such as Still Life, Life Models, Architecture, etc. are experienced first hand, and out-of-class assignments tend to emphasize practice that reinforces in-class activity which, given the constraints of time in a 14 week course, make sense. However, the degree to which students may continue to harbor, and perhaps nurture, approaches to drawing other than those emphasized in observational drawing courses, must be of interest to us.

As observation is the preoccupation of the two levels of Foundation course, we will look there first.

Part of my interest in comparing responses from Drawing 1 and 2 is to understand the degree to which preferences change with experience. Throughout Drawing 1, students will have been immersed in drawing from observation with relatively little attention being afforded to other starting points. Subject matter such as Still Life, Life Models, Architecture, etc. are experienced first hand, and out-of-class assignments tend to emphasize practice that reinforces in-class activity which, given the constraints of time in a 14 week course, make sense. However, the degree to which students may continue to harbor, and perhaps nurture, approaches to drawing other than those emphasized in observational drawing courses, must be of interest to us.

As observation is the preoccupation of the two levels of Foundation course, we will look there first.

|

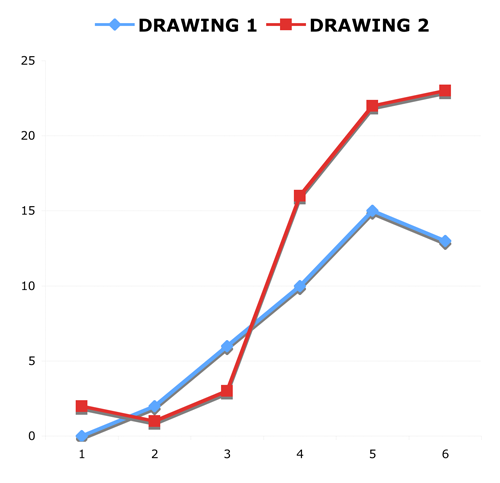

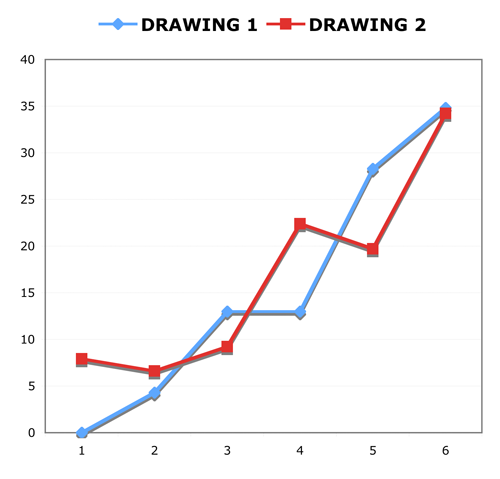

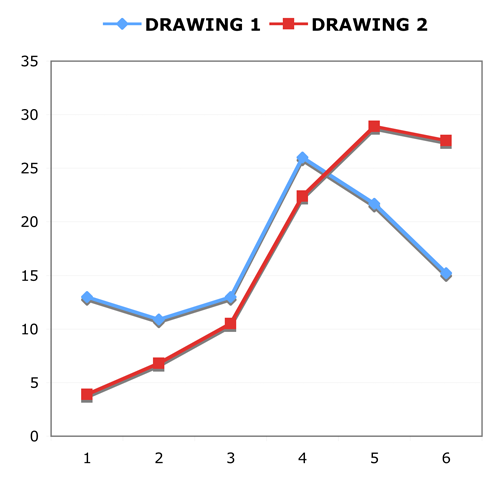

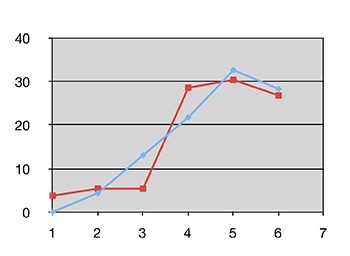

Drawing from observation – comparison While it is interesting to note that a couple of students have decided that their interest in drawing from observation has waned entirely, it is clear that the majority of students have made a significantly greater commitment to this approach that is reported at the first level.We will look next at imagination as that category elicited responses that were closest to those for observation. |

|

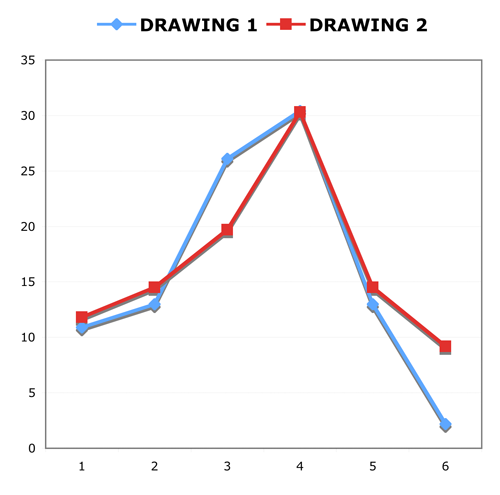

Drawing from memory – comparison This may be the least clear in terms of approaches to drawing in that it is a somewhat hybrid approach. But Drawing from Memory is something that has interested some art educators and has a role in their teaching. As an activity it bridges the gap between observation and imagination in that the drawer is both informed by, and yet separated from, the act of observing. Likewise, the more emotive aspects of mere imagination are tempered by the experience of observation. The responses from both groups of students suggest that there is not much change in interest and that a significant number are neither strongly committed to, or indifferent to, the practice. |

|

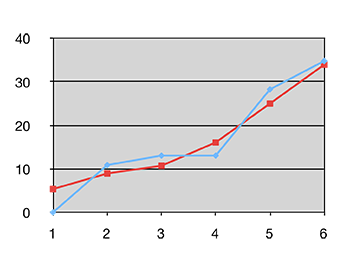

Drawing from 2D sources – comparison Whether as a result of instruction or simply through finding that 2D sources can be useful beyond mere copying, there appears to be a significant increase in the importance placed upon this resource. At the second level, fewer report 2D sources to be of no interest and significantly more express interest. |

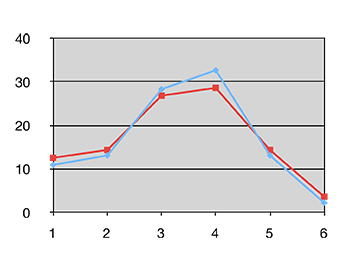

Placing a value on drawing

Finally, students were asked “Which statement best applies to you?’

Finally, students were asked “Which statement best applies to you?’

|

|

A. DRAWING INTERESTS ME A LOT. I SEE IT AS INTEGRAL TO MY FUTURE

B. DRAWING INTERESTS ME SOMEWHAT. IT IS USEFUL IN A GENERAL WAY C. DRAWING ONLY INTERESTS ME A LITTLE D. DRAWING DOESN’T INTEREST ME AT ALL |

Of all the questions, this is perhaps the most loaded in terms of what a response may suggest about an individual’s commitment to the drawing course at hand. Even with reassurance that self-identifying a low rating would not prejudice the instructor’s view of the student’s potential for success in the course, it is certainly possible that some students may exaggerate the importance that they place on drawing.

Of the 46 students from Drawing 1, 34 (74%) self-identified as A; 12 (26%) as B and nobody selected C or D. This should not be surprising as one would hope that students at the very beginning of their studies would see every aspect of their course work as having the potential to excite and inform them.

The 76 students beginning Drawing 2 were a little more reserved in terms of their appreciation and expectations. 42 (55%) chose A; 30 (39%) . 3 students chose C and 1 was brave enough to declare that it held no interest whatsoever.

What can be learned from these surveys?

First, a declaration of bias:

My own art training was firmly grounded in observational drawing and, as such, has constituted an unassailable commitment to observational drawing as the optimum base from which to grow visual arts practices. The 1960’s art school experience, one that saw me majoring in photography and painting, included more time spent drawing than was scheduled for any other endeavor. Such was the commitment to drawing and, had I been asked to fill out my own questionnaire at the time, I am pretty certain I would have rated my interest highest in every category that emphasized the value of observation over all other forms for drawing.

Now, as a drawing instructor some 40 years later, when I take stock of the choices and challenges I present to my students, I do so cognizant that many things that have an impact upon our particular corner of the universe have changed. New technologies have spawned new art forms, new learning environments and, not surprisingly, new student expectations. The visual world of today’s art student has been populated by many more bells and whistles together with the promise that emerging technologies will do a better job and will almost definitely do it much ‘easier’ and much faster. In terms of expectations, this can represent a striking contrast to the analogue, real-time world of a student scheduled to draw for many hours from stationary subject matter: the model for which I was exposed as a student, and the model to which, as an instructor, I have been inclined to adhere.

Moving on

Unscientific though they may be, the surveys confirm that drawing from observation continues to inform and occupy students in ways that seem to be rewarding and useful. However, unlike my own post-secondary experience where it was “observation or nothing, current student interests and experiences suggest that we all may benefit from a loosening of the reins.

I now regularly integrate non-observational elements into first year drawing exercises and do so for several reasons that include:

1. lessons learned in strictly analytical settings can be applied and tested synthetically.

2. stepping back from the strictly observational provides further permission for each student to be innovative in terms both of the aesthetic as well as the technical. Often, we speak of the need for students to loosen up but do so within the context of tight subject matter that, while interesting and challenging in a positive way to the experienced, may be debilitating to the novice; and

3. even while working under the umbrella of observational drawing, allowing for imagination to play a part can encourage a greater sense of ownership. Assigned tasks invite owned responses and elevate critiques to a new and useful level. A student who has adhered to the spirit of the assignment but has stepped sideways to introduce appropriated or imagined elements must see that choices have been made and that choices must have involved decisions, i.e. stuff we can talk about. Instructors who have tried to generate discussion in the context of 20 near-identical and purely objective responses to an assignment will recognize the benefits that flow from thematically influenced variety. Moving beyond mere depiction can have its advantages.

As an instructor of first year drawing, I have adapted from the strict, 100% commitment to learning through observation to an approach that includes more open-ended, out-of-class assignments intended to invite responses that are less predictable. I began this a few years back and have been pleased by the way students have responded. Those with significant observational drawing skills to build upon welcome the opportunity to challenge themselves beyond the minimum limits of the assigned task. They have permission inject elements that generate a greater sense of ownership. And, for those who may be intimidated by their lack of particular drawing experiences, having permission to incorporate sources – imagination, memory, photographs, etc. – can be the catalyst that advances their understanding of, and comfort with the mastery of illusion that lies at the heart of learning to draw from observation.

Addendum

Twenty four months later, in Fall 2012, a further sampling of 56 Foundation Drawing 1 students were surveyed with results as follows. Figures in blue are as reported above. Figures in red are for the 2012 survey.

First time taking university courses of any kind?

First survey: YES 63.04% NO 36.96%

Second survey: YES 71.5% NO 28.5%

Have you taken non-credit/Cont. Ed drawing clases?

First survey: YES 34.78% NO 65.22%

Second survey: YES 30.5% NO 69.5%

Other than assigned work, do you draw for pleasure?

First survey: YES 95.65% NO 04.35%

Second survey: YES 82.00% NO 18.00%

Drawing interests me a lot: I see it as integral to my future:

First survey: 73.91%

Second survey: 46.43%

Drawing interests me somewhat. It is useful in a general way:

First survey: 26.09%

Second survey: 48.21%

Drawing only interest me a little:

First survey: 00.00%

Second survey: 05.36%

Drawing doesn’t interest me at all:

First survey: 00.00%

Second survey: 00.00%

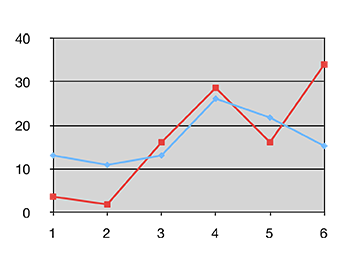

When rating preferences for the different types of stimuli using 0 for Not at all & 5 for very much, the two groups of Drawing 1 compared as follows:

Blue = First Survey

Red = 2012 Survey

Observation

Of the 46 students from Drawing 1, 34 (74%) self-identified as A; 12 (26%) as B and nobody selected C or D. This should not be surprising as one would hope that students at the very beginning of their studies would see every aspect of their course work as having the potential to excite and inform them.

The 76 students beginning Drawing 2 were a little more reserved in terms of their appreciation and expectations. 42 (55%) chose A; 30 (39%) . 3 students chose C and 1 was brave enough to declare that it held no interest whatsoever.

What can be learned from these surveys?

First, a declaration of bias:

My own art training was firmly grounded in observational drawing and, as such, has constituted an unassailable commitment to observational drawing as the optimum base from which to grow visual arts practices. The 1960’s art school experience, one that saw me majoring in photography and painting, included more time spent drawing than was scheduled for any other endeavor. Such was the commitment to drawing and, had I been asked to fill out my own questionnaire at the time, I am pretty certain I would have rated my interest highest in every category that emphasized the value of observation over all other forms for drawing.

Now, as a drawing instructor some 40 years later, when I take stock of the choices and challenges I present to my students, I do so cognizant that many things that have an impact upon our particular corner of the universe have changed. New technologies have spawned new art forms, new learning environments and, not surprisingly, new student expectations. The visual world of today’s art student has been populated by many more bells and whistles together with the promise that emerging technologies will do a better job and will almost definitely do it much ‘easier’ and much faster. In terms of expectations, this can represent a striking contrast to the analogue, real-time world of a student scheduled to draw for many hours from stationary subject matter: the model for which I was exposed as a student, and the model to which, as an instructor, I have been inclined to adhere.

Moving on

Unscientific though they may be, the surveys confirm that drawing from observation continues to inform and occupy students in ways that seem to be rewarding and useful. However, unlike my own post-secondary experience where it was “observation or nothing, current student interests and experiences suggest that we all may benefit from a loosening of the reins.

I now regularly integrate non-observational elements into first year drawing exercises and do so for several reasons that include:

1. lessons learned in strictly analytical settings can be applied and tested synthetically.

2. stepping back from the strictly observational provides further permission for each student to be innovative in terms both of the aesthetic as well as the technical. Often, we speak of the need for students to loosen up but do so within the context of tight subject matter that, while interesting and challenging in a positive way to the experienced, may be debilitating to the novice; and

3. even while working under the umbrella of observational drawing, allowing for imagination to play a part can encourage a greater sense of ownership. Assigned tasks invite owned responses and elevate critiques to a new and useful level. A student who has adhered to the spirit of the assignment but has stepped sideways to introduce appropriated or imagined elements must see that choices have been made and that choices must have involved decisions, i.e. stuff we can talk about. Instructors who have tried to generate discussion in the context of 20 near-identical and purely objective responses to an assignment will recognize the benefits that flow from thematically influenced variety. Moving beyond mere depiction can have its advantages.

As an instructor of first year drawing, I have adapted from the strict, 100% commitment to learning through observation to an approach that includes more open-ended, out-of-class assignments intended to invite responses that are less predictable. I began this a few years back and have been pleased by the way students have responded. Those with significant observational drawing skills to build upon welcome the opportunity to challenge themselves beyond the minimum limits of the assigned task. They have permission inject elements that generate a greater sense of ownership. And, for those who may be intimidated by their lack of particular drawing experiences, having permission to incorporate sources – imagination, memory, photographs, etc. – can be the catalyst that advances their understanding of, and comfort with the mastery of illusion that lies at the heart of learning to draw from observation.

Addendum

Twenty four months later, in Fall 2012, a further sampling of 56 Foundation Drawing 1 students were surveyed with results as follows. Figures in blue are as reported above. Figures in red are for the 2012 survey.

First time taking university courses of any kind?

First survey: YES 63.04% NO 36.96%

Second survey: YES 71.5% NO 28.5%

Have you taken non-credit/Cont. Ed drawing clases?

First survey: YES 34.78% NO 65.22%

Second survey: YES 30.5% NO 69.5%

Other than assigned work, do you draw for pleasure?

First survey: YES 95.65% NO 04.35%

Second survey: YES 82.00% NO 18.00%

Drawing interests me a lot: I see it as integral to my future:

First survey: 73.91%

Second survey: 46.43%

Drawing interests me somewhat. It is useful in a general way:

First survey: 26.09%

Second survey: 48.21%

Drawing only interest me a little:

First survey: 00.00%

Second survey: 05.36%

Drawing doesn’t interest me at all:

First survey: 00.00%

Second survey: 00.00%

When rating preferences for the different types of stimuli using 0 for Not at all & 5 for very much, the two groups of Drawing 1 compared as follows:

Blue = First Survey

Red = 2012 Survey

Observation

Imagination

Memory

In each of these three categories of stimuli, the patterns are similar and collapsing the top 3 preference ratings (3,4&5) show percentage variations as follows: Observation 03.10%; Imagination -01.08; Memory -01.39.

However, the interest in drawing from 2D sources such as photographs, indicates significant difference: an increase of 15.52%

2D Sources

In each of these three categories of stimuli, the patterns are similar and collapsing the top 3 preference ratings (3,4&5) show percentage variations as follows: Observation 03.10%; Imagination -01.08; Memory -01.39.

However, the interest in drawing from 2D sources such as photographs, indicates significant difference: an increase of 15.52%

2D Sources

Commenting on the first set of responses, I noted surprise that there didn’t seem to be a greater preference for drawing from 2D sources, and I speculated that perhaps this was indicative of “changing patterns in instruction (in high school) and, therefore changing student experience and expectations. However the current survey, where preference at levels 3,4&5 totalled 78.57%, would seem to suggest a return to earlier expectations.

Also of note is the -27.48 swing away from identifying drawing as ‘interesting me a lot’ and as ‘integral to my future.’. While somewhat balanced out by the 22.12% increase in ‘Drawing interests me somewhat. It is useful in a general way’, the fact that so many fewer students were disinclined to choose the more passionate response may be a cause for concern. Happily, the number of students indicating zero interest in drawing remained unchanged: zero.

– Bryan Maycock, January 2012